Complexity theory challenges the dominant tradition of what is deemed ‘scientific’ and ‘professional’. It questions whether we can act as if the world behaves like a machine – is predictable, can be divided into parts, and defined by unambiguous cause-and-effect links. Complexity theory emphasises that the social and natural world is organic, systemic, shaped by history and context. Things are affected by many causes and connections and these act together, synergistically. The future emerges, cannot entirely be known in advance. What happens next is affected by history, chance, choice, and the particularity of the local context.

Complexity theory challenges the dominant tradition of what is deemed ‘scientific’ and ‘professional’. It questions whether we can act as if the world behaves like a machine – is predictable, can be divided into parts, and defined by unambiguous cause-and-effect links. Complexity theory emphasises that the social and natural world is organic, systemic, shaped by history and context. Things are affected by many causes and connections and these act together, synergistically. The future emerges, cannot entirely be known in advance. What happens next is affected by history, chance, choice, and the particularity of the local context.

Complexity theory suggests that organisations and markets and ecologies and communities are:

- Organic: They have more in common with ecosystems, with evolving organisms than with machines; they are not in general predictable or controllable.

- Self-organising and comprised of temporary patterns of relationships: They often display patterns of relationships (such as ways of working in organisations or buying patterns in markets) which can be relatively stable but still display some variation and fluctuation and may indeed evolve, eventually, into new patterns.

- Contingent on history and context: The future depends on the detail of what happens, does not smoothly follow from the past.

- Affected by multiple causes: In general there are no simple cause-and-effect chains; outcomes are influenced by several factors acting together, together with the effects of chance, history and the wider environment.

- Co-evolutionary: Organisations are shaped by their environments and vice versa; there is interaction and reflexive change between scales, between actors.

- Episodic, non-linear change: Sometimes current patterns are resilient but flexible, sometimes locked-in and rigid, sometimes change can be fast and radical.

- Emergent: Change can lead to the emergence of features qualitatively different from the past.

The underlying premise is that the complexity of the world is something to be embraced – not ignored or seen as problematic. To assume things are stable and predictable when they are not does not lead to success. And diversity and complexity are necessary, lead to resilience and adaptability. Allowing diversity and multiple pathways ensures things have not become so efficient that there is little potential to be flexible, to adapt if things change, as they inevitably do.

Ode ‘ere

The Wiltshire folks were in a dither

Because of Heraclitus’ river

They knew they could not cross it twice

But were not clear would once suffice?

And then at last a quite astute ‘un

Remembered dear old Isaac Newton

Who was a marvel in his season.

And never was he contradicted,

He said that all could be predicted

And we could all rely on Reason.

And so they dropped all their ferment

And settled on Enlightenment

And all would have continued charmin’

Apart from that annoying Darwin

And his ideas of Evolution

For which, it seems theres no solution.

This led to quite a sense of urgenc-

Y and focus on emergence;

The physicists tried to ignore it

The social scientists deplored it!

The Christians were not too keen

But then into this sorry scene

Came the Russian Belgian Prigogine

Who said, “Don’t fear, science isn’t broken

‘Cos things thought closed are in truth open;

There is a theory quite supreme

Which fits experience like a dream.”

The Wiltshire folk who’d felt at sea

Poured yet another cup of tea

And marvelled at Complexity.

Jean Boulton, 2009

In relatively stable situations, patterns of relationships tend to form friendship groups, political norms, organisation culture, who buys what from whom, and in ecologies (and corporate finance) who eats whom! But these patterns are constantly at threat of being destabilised by events, by variations in behaviour, by shocks, by shifting alliances, by new technologies. So the future depends on the extent to which the status quo is affected by such ‘events’. It is dependent on the particular path, the particular sequence of events; what emerges depends on the precise combination of factors and cannot be predicted in advance nor understood through looking at averages and stable conditions.

In relatively stable situations, patterns of relationships tend to form friendship groups, political norms, organisation culture, who buys what from whom, and in ecologies (and corporate finance) who eats whom! But these patterns are constantly at threat of being destabilised by events, by variations in behaviour, by shocks, by shifting alliances, by new technologies. So the future depends on the extent to which the status quo is affected by such ‘events’. It is dependent on the particular path, the particular sequence of events; what emerges depends on the precise combination of factors and cannot be predicted in advance nor understood through looking at averages and stable conditions.

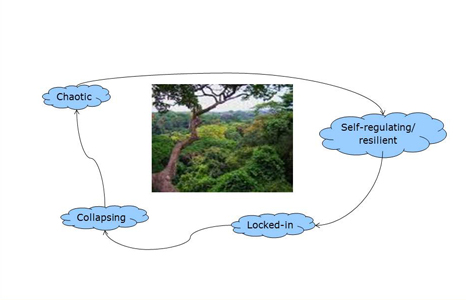

Judging the context

One of the factors to consider in deciding how to operate in a complex world is to judge the nature of the context. The lifecycle of a forest, building on Holling’s work goes through different phases. As it grows and matures it becomes resilient, with multiple pathways, options as to who eats what and whom, variation over the range of the forest. Over time, it becomes more ‘efficient’, less diverse and less resilient, with fewer options, fewer alternative pathways to be able to adapt if things change. This is the ‘lock-in’ stage. This is often followed by collapse as the forest is unable to deal with shocks and change. And the next phase is chaos, with lots of diversity but few established pathways and relationships. Applying this thinking to the social world suggests the following strategies.

| Self-regulating | Experiment | |

| Encourage diversity, keep some slack | ||

| Allow some variation in approach | ||

| Lock-in | Explore what will break the lock, allow innovation and new entrants | |

| Chaos | How to cohere emerging structure, build stability |

I am old enough to remember how we used to work before the current ‘managerialist’ tendencies set in, and it was pretty much as you advocate (in terms of understanding change, working from the bottom-up, and relating to the bigger picture). Your description of the application of complexity theory is really a description of what ‘good participatory management’ should be all about.

I am old enough to remember how we used to work before the current ‘managerialist’ tendencies set in, and it was pretty much as you advocate (in terms of understanding change, working from the bottom-up, and relating to the bigger picture). Your description of the application of complexity theory is really a description of what ‘good participatory management’ should be all about.

Understanding the complex world, and understanding the science and theory that informs this, has been a burning interest of mine for many years. As a physicist turned social scientist, my interest is in getting to grips with the lessons from this ‘evolutionary science’ of ‘open systems’ and seeing what they may mean for the social and natural world, and how they impact organisations as well as affect us as ordinary people living our lives.

There are many articles, papers and references in the Resources pages which give much more information about these ideas. For straight forward introductions read Leadership in a complex world or Managing in an Age of Complexity.

This Interview with Peter Allen, to whom I owe a great deal, is a great summary of complexity and explains some of the history.